Thoughts on the Chinese view of politics and its distinctive philosophy

The principles of “正治” (righteous governance) and “民心” (the will of the people) remain relevant as China navigates those complex international relationships and domestic challenges.

A reader recently asked me what is the Chinese understanding of "politics." To be honest, this is such a broad question that it’s difficult for me to speak on behalf of all Chinese people. However, I find the topic intriguing, so today I’ll share some personal thoughts based on my understanding of Chinese culture and philosophy as they relate to the concept of "politics."

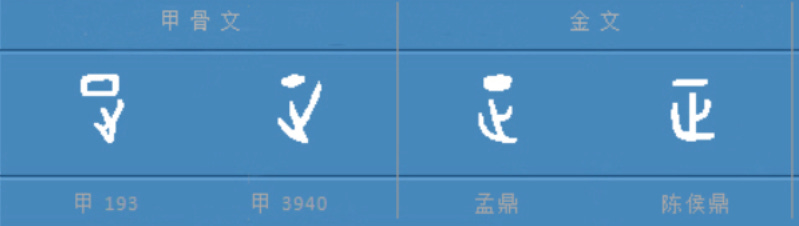

To begin, if you approach the Chinese term for "politics"—“政治” (zhèng zhì) — from the perspective of "训诂学" (Chinese philology), you will find that it is, in a sense, derived from the older concept of "righteous governance"—“正治” (zhèng zhì). This is a dual result of the evolution of Chinese characters and the historical development of thought.

The key to understanding the term “政” (zhèng) lies in the character “正” (zhèng). As Confucius said in The Analects:

"政之为言,正也,所以正人之不正也。德之为言,得也,行道而有得于心也."

"Politics, in its essence, is about righteousness, for its purpose is to correct what is wrong in people. Virtue, in its essence, is about attainment; it is the practice of the Way that leads to inner fulfillment."

This statement reflects Confucius’ understanding of politics and morality, and it is of great significance to Chinese conceptualizations of politics. Here, "政" (zhèng) does not merely refer to politics in the modern sense, but also encompasses the concepts of law, order, and governance.

Confucius believed that only in a society that is fundamentally just, reasonable, and orderly can people be treated equally. Without such an environment, individuals might abuse power and position to serve their own interests, thereby disadvantaging the poor, the weak, and the powerless, who become vulnerable to exploitation and oppression.

In the Dao De Jing, the Daoist classic, there is also mention of the idea that “以正治国”, which translates roughly as "govern the state with righteousness (zhèng)."

Actually, the character “正” is deeply embedded in Chinese culture and daily life. In Chinese, important occasions call for "正装" (formal attire), the main meal is referred to as “正餐” (proper meal), and the room facing the main gate is called "正屋" (the main room). We also have terms like "正坐" (sitting properly), "正确" (correct), and "指正" (to correct), all of which emphasize the significance of “正” in Chinese cultural framework.

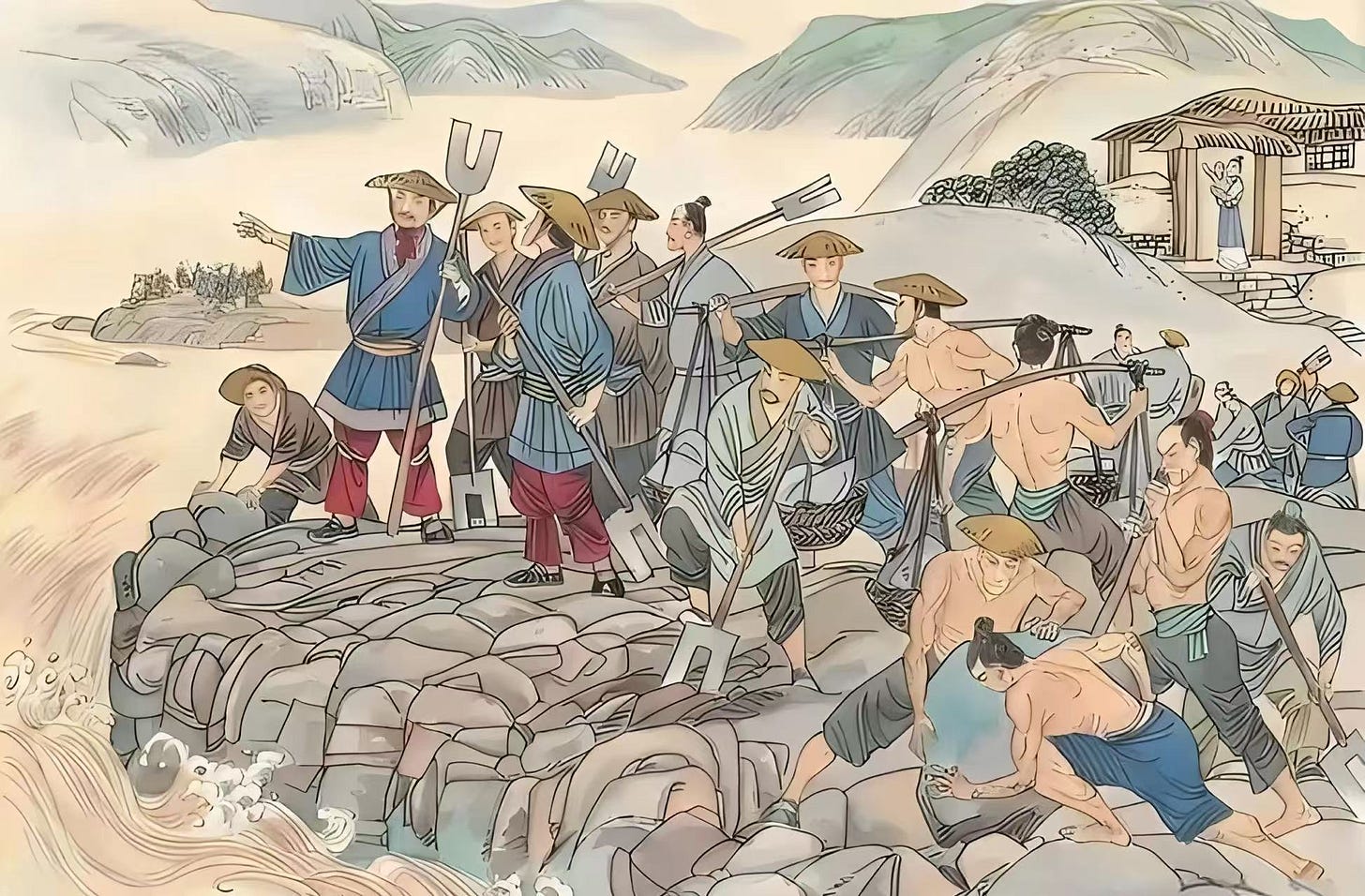

Now, turning to the character “治” (zhì), its historical roots also provide valuable insight into Chinese political thought. Throughout Chinese history, particularly in the face of natural disasters such as floods, there has been a strong emphasis on prevention and preparing for the unexpected.

Yu the Great, around 2000 BCE, successfully controlled the floods, laying the foundation for Chinese flood management and becoming a symbol of perseverance and selflessness in Chinese culture.

This approach is reflected in the concept of “治,” which, in its original form, refers to the management or regulation of water systems. The character itself, shaped with a reference to water, suggests the idea of management from the most basic level—where things begin—just as water is best controlled at its source. Thus, the character "治" symbolizes a methodical and preventive approach to governance.

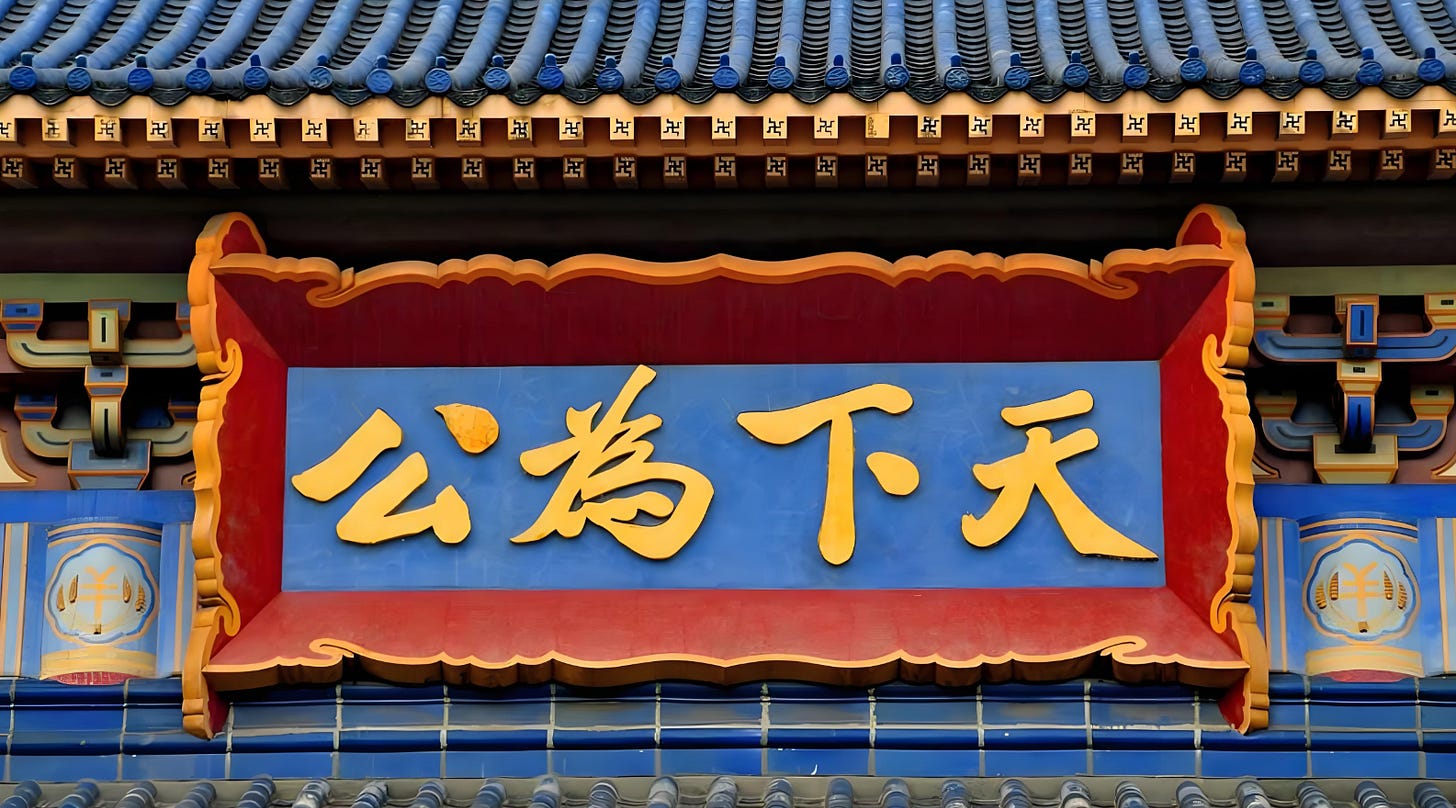

It should be noted that not all schools of thought in China offer the exactly same interpretations of "正治“ (righteous governance). Confucianism emphasizes the integration of personal cultivation with political responsibility, as seen in the maxim “修身齐家治国平天下” (cultivate oneself, harmonize the family, govern the state, and bring peace to the world). Daoism advocates for "无为而治” (governing by non-action), suggesting that rulers should align with the natural order and minimize interference. Legalism stresses the combination of law, strategy, and power, with the ultimate goal still being the achievement of social stability and justice. These ideas, to varying degrees, are inspired by the concept of “天下为公” (All under Heaven, or the world, is for all), which reflects the public and moral nature of politics in Chinese culture.

The concept of "Tianxia" (天下), often translated as "All under Heaven," is central to Chinese political philosophy. Historically, it refers to a political worldview where China sees itself not as a hegemonic power but as a central, harmonious entity, capable of bringing stability and peace to surrounding nations. This model contrasts with the Western concept of nation-state sovereignty, emphasizing cooperation and mutual benefit rather than territorial dominance. The ideal of "Tianxia" speaks to a political vision grounded in shared well-being and moral order.

大道之行也,天下为公

The path of great virtue is such that the world is for all

"大道之行也,天下为公" expresses the highest political ideal: that the governance of society should be based on the principle that the world belongs to all. This shows that China has long opposed the notion that a strong nation must dominate others, and rejects the zero-sum mentality of "win or lose." Instead, “天下为公” advocates for mutual cooperation, harmony, equality, and shared development.

With the establishment of the imperial bureaucracy during the Qin and Han dynasties, the term "正治“ (righteous governance) further evolved into a more specialized concept “政治” (politics). In historical texts such as the Han Shu (Book of Han) and Shi Ji (Records of the Grand Historian), the term “政治” became associated with a broader system of governance, reflecting the institutionalization of statecraft and the bureaucratic structures that supported it.

By this time, "politics" had moved beyond the general notion of governance to refer specifically to the systems, laws, and structures that defined statecraft in the context of the imperial state.

In contemporary China, politicians often speak of “民心” (people's support, or the will of people) as the highest form of "politics" (“民心是最大的政治”). This concept is also deeply rooted in Chinese tradition, as evidenced by the ancient saying which comes from the Shang Shu (Book of Documents), a compilation of 58 chapters detailing the events of ancient China.

民为邦本,本固邦宁

The people are the foundation of the nation; a stable foundation leads to a peaceful country

"民为邦本,本固邦宁" mentioned in Shang Shu reflects the profound recognition of the power of the people by ancient Chinese statesmen, as well as their deep concern for the long-term stability of the state.

The "people-centered" philosophy remains an essential component of Chinese political culture and continues to influence contemporary political discourse. It serves as a reminder to leaders to always consider the needs and interests of the people, and to ensure that policies and actions align with the will of the populace. Only when the state genuinely cares for its people and guarantees their rights and well-being can it earn the trust and support of the people, ensuring the long-term stability of the state.

This idea has been further enriched by proverbs and idiomatic expressions such as “载舟覆舟” (the boat can carry or capsize the boat) and “水能载舟亦能覆舟” (water can carry a boat, but it can also capsize it), which vividly express the decisive role of the people in the governance of the state. These expressions not only underline the importance of the people but also reinforce the inherent power balance between rulers and their subjects in the Chinese political system.

In today's world, the deficits in peace, development, and governance pose significant challenges to humanity. Of these three "deficits," governance is the root cause. The issues of peace and development largely arise from this governance deficit, as the current global governance system, rules, and capacities are insufficient to effectively tackle global challenges, resulting in disorder at the international level. Politicians risk descending into “歪治” (corrupt governance), with ordinary people bearing the brunt of the consequences.

In such an environment, the principles of “正治” (righteous governance) and “民心” (the will of the people) remain relevant as China navigates those complex international relationships and domestic challenges. The focus on “people-centered” politics can be seen in the government’s emphasis on multilateral cooperation in areas such as economic development, poverty alleviation, and response to climate change.

The question of which aspects of China’s practices other countries can learn from and which may be difficult to adopt is another matter. However, I hope we can find more common ground between China’s governance wisdom, historical experience, the spirit of the times, and current realities, while identifying the greatest common denominator between China’s governance principles and those of the West and other civilizations, in order to steer global governance toward a more just and rational direction.