Ancient fishermen's manuals as historical evidence of China's sovereignty over South China Sea

Geng Lu Bu (更路簿), or Manuals of Seaways, was a navigation guide used by Hainan fishermen for the routes between the coast of the Hainan Island and the islands in the South China Sea.

Hello. Today, we’re excited to introduce a fascinating, lesser-known topic — the historical local documents depicting Chinese fishermen's work and lives in the South China Sea.

Recently, we visited Hainan Province, a popular tourist destination in south China. Hainan is renowned not only for its stunning tropical seascapes — which are unique in China — but also for its rich history and culture. This includes Southeast Asian-inspired architecture and the enduring fishing traditions of the Hainan people.

For centuries, fishermen from Hainan have set sail across the South China Sea. While modern times offer many other ways to make a living, some people continue to uphold the fishing tradition, while others preserve and promote it in different ways.

On Hainan’s east coast, facing the South China Sea, lies Tanmen Township in Qionghai City — one of the province’s most famous fishing ports. At the port's entrance, we discovered a privately owned gem: the Geng Lu Bu Museum.

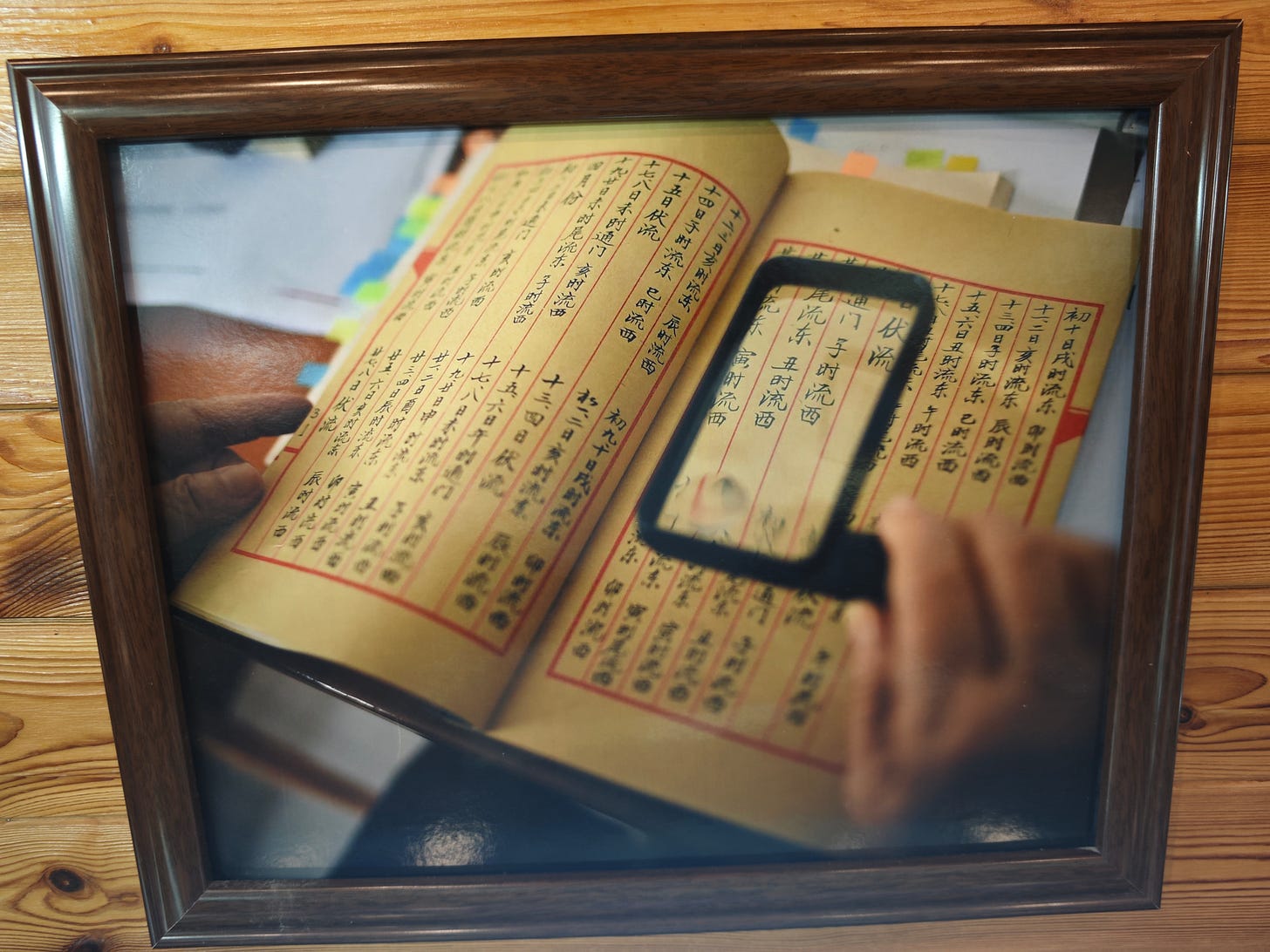

Geng Lu Bu (更路簿), or Manuals of Seaways, is our topic today. It was a navigation guide used by Hainan fishermen for the routes between the coast of Hainan Island and the islands in the South China Sea. Geng in Chinese is a length unit that one Geng is equal to 10 nautical miles, Lu means routes and Bu means books or manuals.

Written in Hainan dialects and passed down from generation to generation, Geng Lu Bu are no longer navigation manuals but historical documents. Some fishing families still retain handwritten copies of Geng Lu Bu, yellowed with age, even though modern practices have long supplanted traditional fishing methods.

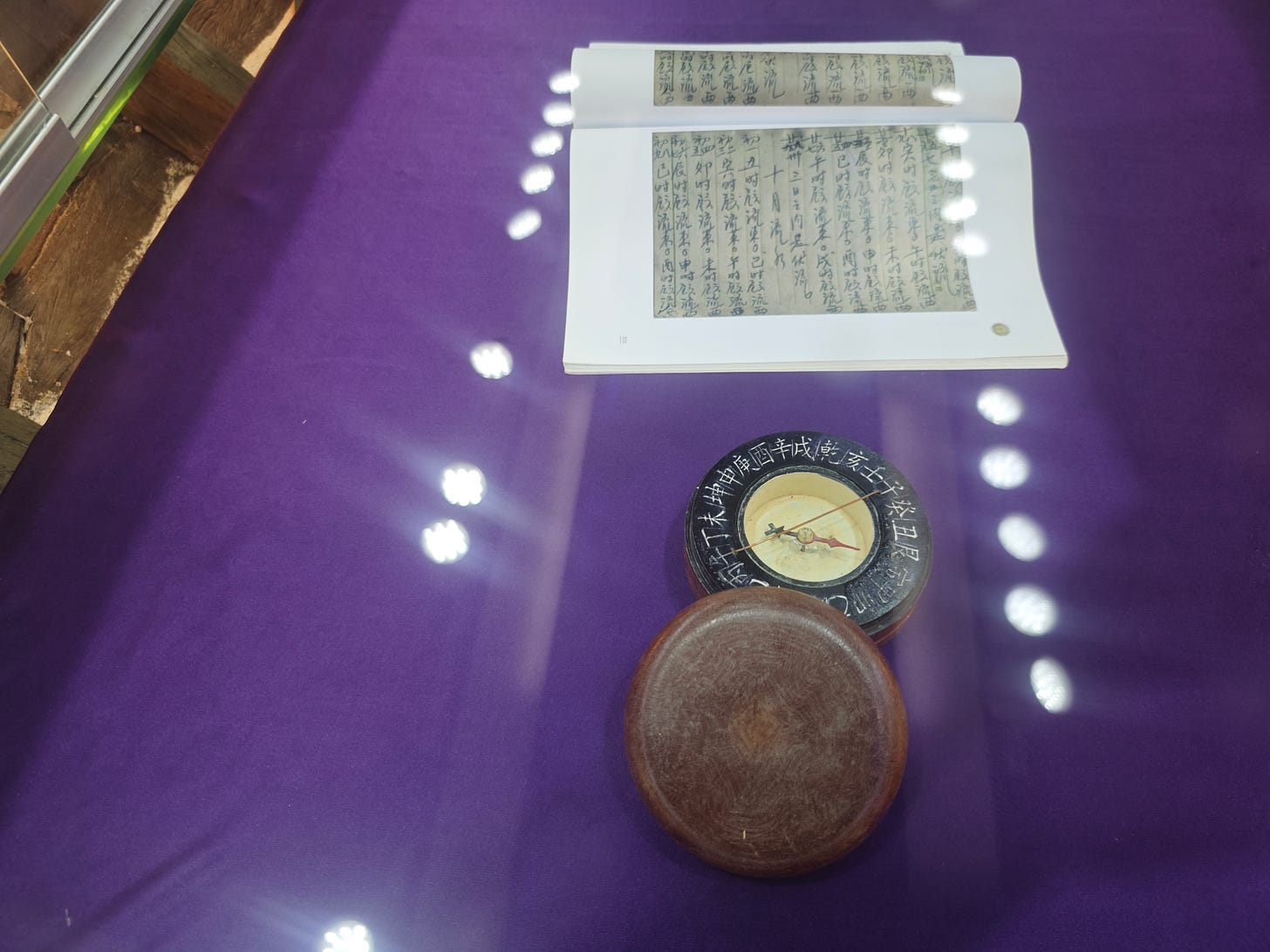

Some original Geng Lu Bu manuals are exhibited in the museum, some can date back to over 100 years ago. Wang Zhenzhong, founder of the museum and owner of a handicraft factory, was born in a fishing family in 1977. Both his grandfather and father are skilled fishing boat captains, and he has also sailed to Nansha Qundao (Nansha Islands). He collected his family's fishing tools at the museum, including fish spears, navigation maps, compasses, and also original Geng Lu Bu manuals passed down from his ancestors.

Wang Zhenzhong and his Geng Lu Bu Museum

He showed us a book, with wrinkled and broken pages, on which his ancestors wrote "自大谭去船岩尾用乾巽十五更收." "大谭," Da Tan, is a deep pool outside of the Tanmen port, "船岩尾," Chuan Yan Wei, is an island in the South China Sea, "乾巽," Qian Xun, is a direction marked on China's ancient compass, and "十五更," means 15 Gengs (about 150 nautical miles). The sentence means that from Da Tan to Chuan Yan Wei goes in the direction of Qian Xun for 150 nautical miles.

The manual covers not only sea routes but also weather conditions, wind directions, and ocean currents for different times of the year. For example, it warns against setting sail on the 3rd day of the 3rd lunar month, the 8th day of the 4th lunar month, and the 19th day of the 6th lunar month. Wang recalled that in the late 1980s, his father set out to sea on one of these dates — and the ocean was truly vast and treacherous.

"He barely made it back to shore," Wang said.

In 2008, Geng Lu Bu was recognized as part of China’s national intangible cultural heritage. Later, in 2018, Wang Zhenzhong's father, Wang Shubao, was honored as an official inheritor of this heritage by China’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

For thousands of years, Wang's ancestors and other Hainan fishermen endured the heat of the scorching sun and braved the stormy seas, mapping submerged and treacherous ocean currents to find the routes across the vast, unmarked surface of the roiling South China Sea. They found, stationed and developed many islands and reefs and named them, in the Hainan dialect.

The manuals were excluded for fishing boat captains and were edited and rewritten every generation. With Geng Lu Bu, a compass and an incense burner, fishermen could set sail through the South China Sea.

An ancient Chinese compass and a photocopy of Geng Lu Be manuals

At the bow of the fishing boat, fishermen would light a stick of incense inside a wind-protected burner. The incense took about two hours to burn out, allowing them to track time.

Hainan fishermen have lived and worked in the South China Sea islands since ancient times, so the names of many islands and reefs were first named in the Hainan dialect.

Wang Zhenzhong vividly recalled his first voyage to the South China Sea with his father when he was around 18 years old. "The view was incredible! Sitting on the boat, I could see the crystal-clear coral sea beneath me," Wang said. Despite the breathtaking scenery, he suffered from seasickness and vomited for most of the journey.

Wang learned the art of fishing in coral reefs from his father and other seasoned fishermen. Wearing a mask and breathing tube, they would dive 20 to 30 meters below the surface. Experienced fishermen could hold their breath for up to five minutes. Using fish spears or even their bare hands, they would catch sea cucumbers, lobsters, abalone, and fish hiding within the reefs.

However, valuable fish like groupers cannot be speared, as any injury would reduce their market value. Instead, fishermen use a natural anesthetic derived from the stems and leaves of a plant to temporarily stun the fish. The stunned fish then float to the surface, where they are carefully collected.

"Fishermen have always fished this way, passing down the tradition from generation to generation. Even today, the South China Sea is like our vegetable garden. We farm the sea and go fishing," Wang explained.

Wang Zhenzhong is introducing his family's original Geng Lu Bu manual.

"Every man in Tanmen is expected to be a fisherman!" said Fu Minglin, born in 1980, a fisherman-turned-B&B owner. "Going out to sea is incredibly cool! In Tanmen, unless you're very timid or in poor health, everyone heads out to sea."

Fu has more experience in sailing and fishing than Wang. The Meiji Jiao and Zhubi Jiao, two major reefs of China's Nansha Qundao (Nansha Islands) in the South China Sea, were familiar destinations for him. He also sailed to Huangyan Dao (Huangyan Island) and Zengmu Ansha (James Shoal), China’s southernmost territory.

Fu’s uncle, a skilled captain, could navigate the sea using only Geng Lu Bu manuals and a compass. Fu learned a great deal of sailing experience from his uncle, including how to use the color of clouds to locate islands and reefs. The shallow and deep waters reflect light onto the clouds differently, creating subtle color variations that reveal what lies below.

Fu explained that ancient fishermen had a unique method of measuring their sailing speed: they would throw a jar into the water, and the captain, holding onto the rope, could gauge the speed by feeling the force exerted on it.

Thanks to knowledge passed down through generations, fishermen from Hainan, Guangdong, and Fujian were able to sail across the South China Sea to Malaysia, Singapore, and other Southeast Asian destinations.

During the Age of Sail, a typical fishing journey lasted several months, depending on the monsoons. Fu told us that according to Geng Lu Bu, every year in the twelfth month of the lunar calendar, fishermen rode the northeast wind to the south, and returned in the fourth month of the lunar calendar in the following year when the southwest wind blew.

Fu Minglin and his seaside restaurant.

During the voyage, fishermen stayed on the boat, or lived on islands with fresh water for a long time, leaving behind traces of development and habitation on the islands, which have been preserved to this day.

They often traded some of their catch directly at sea or brought it to Southeast Asia, where many chose to settle permanently. As a result, many fishing ports, including Tanmen, became renowned hometowns for overseas Chinese.

"The South China Sea is our ancestral sea, where our grand-grandparents went, so we go there too," said Fu.

Yan Genqi, a professor from Hainan University who is an expert of Geng Lu Bu, said that the paper-based manuals were formed no later than the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), while the orally transmitted sailing directions had already begun to take shape among Hainan fishermen as early as Song Dynasty (960-1276). Since 1974, researchers have discovered 52 copies of Geng Lu Bu in Hainan.

"The systematic and regular use of monsoons for continuous navigation and fishing activities in Xisha Qundao (Islands), Zhongsha Qundao and Nansha Qundao over hundreds of years is unparalleled by any other country or nation," said Professor Yan.

"It (Geng Lu Bu) serves as compelling evidence that the Chinese were the first to discover, name, develop, and administer the islands of the South China Sea," Yan added.

(Chen Kaizi and Zhong Qun also contributed much to this article.)

The 4th SCSPI-RSIS South China Sea Roundtable Held in Beijing

On November 18, 2024, Kumar Ramakrishna, Director of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, along with his team, visited the “南海战略态势感知计划” South China Sea Strategic Probing Initiative (SCSPI) to conduct the 4th SCSPI-RSIS South China Sea Roundtable. Nine Chinese experts from SCSPI and 6 RSIS experts exchanged views and discussed on current situations in the South China Sea and related issues.

The experts from both sides reviewed recent events in the South China Sea, assessed the current and future situations in the region, discussed issues including international strategic situations, regional security, as well as changes in the South China Sea situation after the US elections, and exchanged opinions on topics such as managing differences, enhancing practical cooperation and promoting negotiations on the “Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC)”.

The representatives from both sides highly praised the dialogue mechanism of the SCSPI-RSIS South China Sea Roundtable and reached a consensus on further deepening exchanges and cooperation.

About SCSPI

With a view to maintaining and promoting the peace, stability and prosperity of the South China Sea, South China Sea Strategic Situation Probing Initiative (SCSPI) was launched in April of 2019. The Initiative aims to integrate intellectual resources and open source information worldwide and keep track of important actions and major policy changes of key stakeholders and other parties involved. It will provide professional data services and analysis reports to parties concerned, helping them keep competition under control, and with a view to seek partnerships.